|

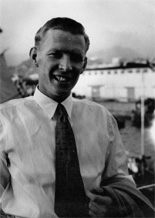

Captain Alexander ('Sandy') J Mackenzie 27th August 1925 - 7th October 2016 |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

Shortly after my father’s illness took grip, and he was admitted to Roxburghe House for palliative care, I became aware of a small travel bag containing handwritten notes about his life and experiences. These appear to have been put together in just the past few years and they form a remarkable record that will be valued by future generations of our family. From this comes the following extract : |

||

|

|

'THE THINGS YOU REMEMBER' FIRST TRIP TO SEA 1942 It was not easy to get an apprenticeship in the British Merchant Navy and even in wartime preference was given to applicants who had been to a pre-sea training school. Direct entry was rare and usually involved some “string pulling”. My sponsor was a family friend, the widow of an American Chartered Accountant who had been financial adviser to Butterfield and Swire, Hong Kong Agents of “The Blue Funnel” Line (also known as Alfred Holt & Co.), the company in which I served 14 years. I was interviewed by Holt’s in Birkenhead in early 1941 some months before my 16th birthday. I was accepted and given the option of either commencing when I became 16 or going back to school for another year to take my Scottish Higher Leaving Certificate. I decided to return to school. I notified Holts in 1942 when I learnt I’d passed the exam and not long afterwards was told to report to Liverpool, after I’d done a month long course at the Outward Bound Sea School at Aberdovey, in Wales, in July. Within a week of reporting for duty, and just before my 17th birthday, I was the “first tripper” of four midshipmen en route to Glasgow with instructions to join the “Maron” at the Tail of the Bank - this is the large anchorage between Dunoon and Helensburgh on the north shore of the Clyde, and Greenock and Gourock on the south, which was the main wartime convoy assembly port in the UK. In failing light the tender which took us out from Gourock Pier mistook the ship we were supposed to join and put us on board an “Empire” boat, a wartime-built standard vessel. Extra radiators were being fitted in the accommodation so we assumed, not too happily, that the ship was bound for an Arctic convoy, to Murmansk. We were rather relieved when the tender came back for us and apologised for mistaking the ship’s identity. We were then taken to “Maron”. “Maron” was a twin-screw motorship, 6,700 Gross tons, 433 feet long, 6 hatches, built in 1930. She was one of a class of 4 sister ships. “Marons” designed speed was 14½ knots. The crew numbered 96. Midshipmen’s accommodation is known as the “halfdeck”, which on the “Maron” was a not too spacious 4-berth cabin on the main deck. The bunks were in two tiers with two storage drawers under each tier. There was a small table in the middle and a compactum for washing in. There was no running water, so a filling can was provided. The doors were all fitted with hinged escape panels and as a further safety precaution, all doors had to be kept hooked and slightly open when at sea. The ship stayed around the Clyde for about 5 weeks, occasionally going up river to load as cargo became available. No one had any idea of where we were bound, although it was obviously military supplies we were loading. On one occasion, when berthed at King George V Dock, I was called to the Chief Officer’ cabin. With the Mate were two civilians who looked me up and down and one said to the other “I don’t think he’s a spy, do you?” Then I was reprimanded for posting a letter in the letter box outside the dock gates when there was an instruction on the ships notice boards – which I hadn’t read – to say that all mail had to be handed to the authorities for censoring. Whilst at anchorage it was very interesting and exciting to see shipping come and go, especially the “Queen Mary” and the “Queen Elizabeth”, the “Aquitania” and other large troopships bringing in American troops. We sailed one evening towards the end of October, still without any knowledge of where we were going. The senior midshipman told me I was to be on the 8 to Midnight watch on the bridge and when I asked him what I was supposed to do, for I hadn’t a clue, he said I was just to report anything unusual that I saw and to run any messages for the officer of the watch, if required. I felt so lost, homesick and useless I think I’d have given up my seafaring career there and then, but we were too far offshore and I couldn’t swim! By next morning the convoy had assembled, ships from various ports, with naval escort, about 75 cargo ships in all. We headed round the north of Ireland, west well into the Atlantic, due south until on the latitude of the Straits of Gibraltar then east towards the Straits. The rumour from the “Galley Wireless” was that we were Malta bound, not a pleasant prospect after the experiences of convoy “Pedestal” in August. To pass through the Straits the convoy was formed into two columns. Passage was arranged for darkness. I think no one could have informed the duty signaller on Europa Point Gibraltar who must have noticed the unlit ships, for a light from there flashed the general challenge - “What ship, where bound”? I wonder how his court martial went?! What a sight next morning! A beautiful crisp, clear day with the snow capped Sierra Nevadas visible on the coast of Spain, but best of all we’d been joined by the legendary Force “H” which had obviously come out from Gibraltar. There was the battleship “Nelson”, battlecruiser “Renown”, three aircraft carriers, several cruisers and many smaller naval ships. We learnt soon afterwards that the operation (Operation “Torch”) was the invasion of North Africa, west from Cape Bon, Tunisia. On the evening of 7th November, many ships of the convoy broke off for Oran. Two ships, “Maron” and “Macharda” were formed into a single line with the heavyweights of Force “H” and carried on to the designated landing zone, which was off Cape Matifu, about 10 miles east of Algiers. After the assault ships were anchored, the ships of Force “H” went further offshore on patrol against any possible intervention by enemy naval forces. By now the enemy were aware of what was happening and we were attacked several times by low flying Junkers 88’s. One ship nearby had its stern blown off, but that was the only casualty I saw at the landings. The Vichy French resistance collapsed quite quickly and “Maron” was ordered into Algiers and in fact was the first merchant ship alongside. This was no doubt because our cargo mainly consisted of cans of Avgas fuel for the fighter squadron which soon became operational. We were there for four days discharging. Shore leave was not allowed so I never set foot ashore on the first foreign port I visited. We sailed from Algiers on the afternoon of 12th November. We formed a small convoy with three other ships in line ahead, with small-ship escort, bound for Gibraltar. I remember the other ships were “Lalande” (of Lamport & Holts) “Macharda” (a Brocklebanks ship ) and “Manchester Merchant” (of the Manchester Lines). Next day was Friday 13th November, traditionally the seaman’s unluckiest date. At the time the midshipmen were on double watches, four hours on duty, four off. I was on the 8 to 12 in the morning with the senior midshipman. After lunch we “turned in”, to catch up with some sleep. I was wakened just after 3pm by Davies, another of the midshipmen, who was in a great state of agitation and who literally pulled me out of my bunk, yelling that the ship had been torpedoed and was being abandoned. Two torpedoes hit the ship and I swear I never heard a thing. I grabbed my panic bag - which was a light bag handy containing a change of clothes and some cigarettes in case of an emergency that someone had advised me I should have - and looked around for my lifejacket which, of course, I’d carelessly left on the bridge at the end of my previous watch! I dashed up to the bridge and as I picked up my jacket, these are my recollections :- The ship was beginning to heel, a tarpaulin was draped over the triatic stay (the wire from the foremast to funnel) having been apparently blown off the No.2 cargo hatch and there was about 6” of water in the wheelhouse, probably due to the explosion. One thing always makes me smile, that is the behaviour of the captain and the quartermaster. Captain Hey said :- “That will do the wheel, quartermaster”, to which the QM replied, “That will do the wheel, sir”, and he bent down and secured the wheel amidships with the small rope toggle used for that purpose at the end of any docking. “Right then”, said the captain, “Abandon ship”. The three of us then went down to our respective boat stations. The ship sank in 7½ minutes from the time the torpedoes hit, all boats were safely away from the ship’s side and there were no casualties. The speed with which the ship was abandoned safely was mainly due to the fact that all lifeboats were swung out, ready for lowering when ships were at sea in wartime. Fortunately the sea was fairly calm too. It took a few minutes to gather my senses when in the lifeboat, for it’s quite a feeling to watch your home sinking stern first. The Chief Steward was in our boat and he happened to say how pleased he was to have saved his case, the one with all the Bar accounts in it. Without a word the 4th Engineer took the Chief’s case and dropped it over the side! We watched the other ships of the convoy disappearing towards the horizon but one of the escorts had been detached to pick us up, which it did after we’d been about an hour in the boats. It was the corvette, HMS “Marigold”. Up until our torpedoing she had been towing some lifeboats rescued from the P&O Liner “Viceroy of India”, sunk the previous day, but when she came along all the boats were cast adrift. We caught up with the convoy again and during the night the “Lalande” was torpedoed but managed to make it to Gibraltar. We stayed in the Hotel Bristol in Gibraltar and were all fitted out with new clothes; all getting similar grey pinstripe suits. Every day a launch took us out round ships at the anchorage to see if we could be found a passage home. Empty troopers were now coming back from the landings. Eventually we went on board the P&O “Mooltan”. We arrived back at the Clyde about 6 days later and on going ashore we were given rail tickets home. I clearly remember getting off the train from Gourock in Glasgow Central Station in the evening along with the other crew members, all obvious survivors, yet the general public scarcely gave us a second look, no doubt because it was such a common occurrence in those days. We all went our separate ways from Glasgow and I was the only person bound north. I arrived home in Lossie about 8 in the morning. For some reason or other I hadn’t phoned to say I was coming so my parents were quite surprised when they answered the door. All my kit was in a cardboard box around which I’d wrapped my lifejacket. I don’t know what I took it home for, a souvenir perhaps.

CM: There were a number of short postscript notes that dad made to this record. These are two of them : Firstly he notes that HMS “Marigold”, the flower class corvette which had rescued the crew of the “Maron”, was bombed and sunk just 4 weeks later, off Algiers, in the late evening of 9th December, with the loss of 1/3 of the crew - 40 men ... Finally he says … “believe it or not, I kept getting letters from the Head Office Catering Department for over a year requesting that I give them an estimate of my bar bill on “Maron” until the time of the sinking. The 4th engineers action in the lifeboat had apparently caused them a lot of trouble!”

|

||

|

|

|||